A family of Afghan refugees arrived in CT. Here's what happened.

March 4, 2025: Qatar to Connecticut

In early March, sitting in his sister’s West Haven apartment, Sayed Rahim Rahim opened the small leather backpack where he carries his family’s documents for safekeeping. He pulled out certificates printed with Afghan and American flags that he received during the 12 years he worked as an automotive mechanic for the U.S. armed forces.

On the rug, he spread out the Qatar Airways tickets and stack of passports that had helped get him, his wife, their son and four daughters across the Atlantic in a hasty departure less than a week earlier.

The family’s arrival in Connecticut coincided with a chaotic new chapter for refugees coming to the United States, as the Trump administration halted new arrivals and began dismantling the services that once supported them. Funding cuts, an end to Temporary Protective Status for immigrants from countries like Haiti and Venezuela, and growing uncertainty for others about their future on U.S. soil have since become features of the national news cycle.

In Connecticut, that chaos has shaken the refugee communities that have called the state home — and the resettlement agencies that have historically contracted with the federal government to lay the groundwork of a successful life in the United States.

Rahim’s family’s crisis-driven arrival may be a harbinger of how the new reality looks for refugees and Special Immigrant Visa holders like him, as support flounders and resettlement groups increasingly turn to private donors and volunteers to fill the gaps left behind.

The uncertainty began for the family in January, when they were readying to fly from a refugee camp in Qatar to the U.S. Along with more than 1,600 other Afghans, the family learned their flight had been abruptly cancelled, an action taken by President Donald J. Trump on Jan. 21, the day after he signed an executive order to indefinitely pause refugee resettlement.

The United States has ushered 200,000 Afghans to safety since the Taliban took control of the country after U.S. forces left in 2021, in what was widely considered a tragically botched exit. Afghans like Rahim, who had worked for the U.S. forces despite risks of retribution from the Taliban, had been promised a safe haven here through the pathway of Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) for him and his family. In Rahim’s case, the cancelled flight came after an eight-year wait for his visa to go through, during which time the radius of his life constricted to keep him and his family safe. For a year, he and his family lived in a hotel room.

Meanwhile, in West Haven, Rahim’s brother-in-law, Noorjan Omerkhel, was shocked when he learned the flight was off. The family began scrambling for a solution.

Rahim and his family were still approved to come to the U.S. as SIVs, and the short-term passports they’d been issued for the trip were valid for a few more weeks. They just needed plane tickets. Omerkhel had lost his job a few months before, but he logged on to Qatar Airways and emptied most of his savings — $6,845.07 — on seven plane tickets.

It was a blow, but Omerkhel had reason to believe that, once the family arrived, they’d be greeted with the same robust support he’d received when he came to the U.S. nine years earlier. He remembered how New Haven-based Integrated Refugee and Immigration Services (IRIS) had taken care of everything, from preparing an apartment, to cooking a first Afghan meal, to enrolling his kids in school and scheduling medical appointments.

But when Rahim’s family arrived on Feb. 26, they met a different reality.

IRIS was in crisis. Omerkhel alerted the group that Rahim and his family were planning to come, but just a few days before they arrived.

Omerkhel brought them back from the airport and took them into his small home with his wife — Rahim’s sister — and their three kids for the first few nights. But he was worried.

“There’s no case manager for (Rahim), he’s seeking help for transportation, his wife is pregnant, and his daughter is having a dental issue.”

He wondered if buying the plane tickets had been a mistake.

“Now it fills me with upset, too much upset inside,” Omerkhel said. “I’m not a governor or mayor … simply put, I’m not (a) financially stable person. I lost my job, and still I’m struggling to find a job.”

Back in January, IRIS had planned to help the family. But those arrangements were made before the organization was thrown into turmoil: Federal contracts worth $4 million were abruptly cancelled, the group was laying off dozens of employees and making the painful decision to give up its primary physical office.

“We were in the midst of heartbreaking meetings,” said IRIS Executive Director Maggie Mitchell Salem.

IRIS was struggling to make sense of its new reality. Over the years, the group had co-signed leases on over 100 apartments. But with the funding to help pay for those apartments gone, they were searching for new housing for clients and working with landlords to transfer the leases to their clients’ names.

Anxious phone calls flooded in from families who had fled war and violence in their home countries, then spent years painstakingly building new lives: learning English, going back to school, finding jobs and friendships in a wildly unfamiliar place. But without citizenship, what might become of those lives? Many of their case workers had lost their jobs and could no longer give them answers.

Amid these calls and meetings, a group of core IRIS staff met in Mitchell Salem’s office in late February to talk about Rahim and his young family.

“I think initially I said, ‘No, we can’t help,’” Mitchell Salem recalled. Their remaining staff was spread thin, and much of their funding had been wiped out. But as they talked, Mitchell Salem began to question herself. This work, she reasoned, was what IRIS had been built to do.

“It’s like — we can still do this. It is absolutely right to do it,” Mitchell Salem said. “The community will have our back, regardless of whether the federal government does.”

The mood seemed to lift. More Afghan families arrived — a total of four families and a single man — and the group put out a fundraising call.

Hewad Hemat, manager of resettlement services at IRIS, and Rona Rohbar, the head of the IRIS health team, were assigned to help the family.

“It was kind of shocking, difficult,” said Hemat, who also came to the U.S. as a refugee from Afghanistan in 2014. “A family with five kids, no credit history, the mother is pregnant and the children are so young! And there is no government help. We were very worried.”

March 7, 2025: Where would they live?

It had been nine days since the family had arrived in the U.S., and they had moved from Omerkhel’s home to stay with Rahim’s brothers and cousin in a cramped two-bedroom apartment in West Haven.

Rahim had met with IRIS earlier that day, and he had signals that the organization was trying to help him, but the predominant emotion was still anxiety about a stack of unsolved problems. Most important among them: Where would they live? Rahim’s relatives had been generous, but it was a lot to ask the three men living on their own to take in a family of seven.

Whatever the obstacles of the day, Rahim’s children always gave him and his wife, Madina, some comic relief. His youngest daughter, Asna, was still working on her walking skills, and she stumbled across the carpet and into his lap. She babbled, then giggled at the tired smile Rahim pasted across his face.

Asra, 3, curled up on a cushion, peering into a YouTube video on a cell phone. Asia, 4, circled the small apartment, on the hunt for something to busy herself. Serwat, 11, and Alia, 6, sat quietly with calm smiles on their lips, listening to their uncle translate questions to their father in his native Pashto. Rahim was beginning to learn English, but he couldn’t speak fluently like his brothers, who had served as translators with U.S. armed forces. Without being asked, Serwat and Alia pitched in, putting away visitors’ shoes or distracting the baby when she cried.

Rahim had met with IRIS for an intake interview. When he went to their office, they gave him a couple of books for the children to explore — a pop-up book with pictures of trucks, another with games and pages of butterfly and princess stickers. At the apartment, the younger kids pulled the books from each others’ hands, anxious to look through them. Asra peeled the bright stickers off the page and pasted them up and down her arms.

It was Ramadan, and the adults were fasting until the evening. Rahim’s wife Madina, who asked not to be photographed, had been feeling weaker than she had during previous pregnancies. Rahim urged her to break the fast and eat during the day, and sometimes she did.

So far, the family hadn’t seen much beyond the walls of their relatives’ apartments. It was chilly out, in the 40’s. In typical New England fashion, the sky vacillated from a blanket of gray to light blue. “They’re too naughty” to take outside, Rahim said of his children with a smile, through his brother’s translation. As in, he wasn’t up for venturing into the unknown with five young kids.

The family had practice hunkering down together in a small space — they had spent an entire year living in a Kabul hotel before getting to the refugee camp in Qatar, confined to the room for their safety.

March 11, 2025: Signs of progress

A few days later, progress: The family had doctors’ appointments, and Rahim and Madina now had their own cell phones, given to them by IRIS, so they weren’t dependent on borrowing relatives’ phones to communicate. IRIS was pulling together money for a few months’ rent, plus the deposit, so they’d be ready when they found an apartment.

His brothers drove for Uber, and the noise of the children sometimes kept them awake. It was time to get their own place.

“IRIS should help us,” Rahim reasoned. His wife was pregnant. Who knew how long it would be before he’d be able to start working?

But his brothers agreed that Rahim’s career as a car mechanic was a stroke of good luck under the circumstances — that particular set of skills transcended borders and language. First, he’d need a driver’s license and an automotive repair license. It was another set of bureaucratic hills to climb.

Rahim spent hours cooking a meal of kabuli pulao, the Afghan national dish of lamb and rice with spices, to break the daily Ramadan fast. Once the family ate, the children curled up together in the corner of the living room, watching videos on his phone.

March 12, 2025: Setbacks and opportunities

Rohbar was in charge of getting the family medical care. Just a few months before, she would have had 11 team members working for her.

“The whole team is gone. I’m the only one left,” Rohbar said.

It was lucky for Rahim and his family that Rohbar was the one left. She was from the same city in Afghanistan — Khost — and she spoke the same dialect, a version of Pashto she said can be unintelligible to people from outside that region.

Rohbar helped the family schedule their medical appointments, but she was spread too thin to stay while a registered nurse checked their hearing and drew blood. Instead, she showed Rahim the number to dial for an interpreter. The connection faded in and out — “Hello? Are you there?” — the nurse asked the voice on the other end of the line. Sometimes, she was.

The kids explored the beds, the walls, the medical supplies, as two nurses examined them one by one. Everyone remarked on the large family — so many kids! Madina stayed at home, resting before her prenatal appointment later in the day. Asra, the 3-year-old, smiled through a hearing test. And somehow Alia, 6, smiled through her blood draw.

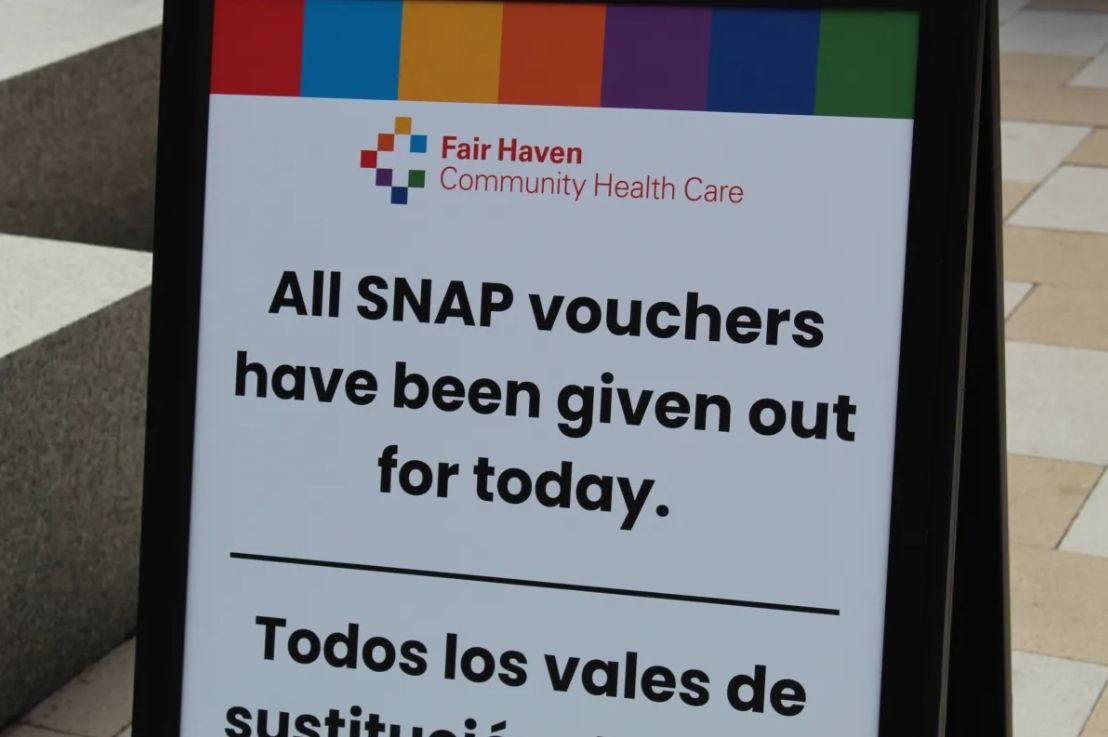

Nurse Lori Wallach asks Sayed Rahim Rahim medical intake questions with the help of a remote interpreter during a visit to Fair Haven Community Health Care on March 12, 2025. Credit: Shahrzad Rasekh / CT Mirror

W hen all of them had been poked and measured, a weary Rahim led the children to the front of the clinic. Within 15 minutes, Rohbar had pulled up in a minivan to take them back to Rahim’s brothers’ apartment.

Rohbar was doing what she could for the family under the circumstances, but she understood the chasm between these services and what she did for refugees just months earlier. In fact, Rohbar herself came as a refugee from Afghanistan 22 years ago as a teenager, and those first moments of welcoming live as vivid scenes in her memory. At the airport, they got off the long flight and were fingerprinted by immigration authorities. “You cannot trust any stranger,” in those early days, but there was a representative there from the International Organization for Migration who helped them through the paperwork, and then gave them bus tickets and guided the exhausted family to their bus. In New Haven, IRIS staff greeted them as they walked into the dark September night.

“The case manager was there with two or three cars, and the apartment was ready. The lights were on. Our favorite meal — the Afghan traditional meal — was on the table. The feast was ready, you know, the Afghan feast. The fridge was loaded with food. I don’t have words to explain the excitement.”

Rohbar kept walking around from one end of the apartment to the other. The beds were made, and the closets were full of clothes. She was fascinated by the food in packages. Back in Afghanistan, they shopped in markets — she’d never seen the boxes and clamshell plastic that fills American supermarkets. “To me that was so interesting! I couldn’t believe it was real.”

And the dish they’d prepared amazed her. It was kabuli pulao. Rohbar had spent years learning to make the recipe from her mother, but her attempts were met with criticism. She never got it quite right. Yet somehow, these strangers across the world knew how to make the dish.

That night still ranks as the happiest of Rohbar’s entire life.

“Whenever I’m upset, these memories keep me alive,” Rohbar said. “I can still feel the joy from that night.”

When Rohbar looked at Rahim and his family — one man, one boy, a woman and four girls with another baby girl on the way — she felt a responsibility, and an excitement, to lead by example.

As a woman, “it’s so shocking to them that I’m speaking in English, I’m working, I’m driving and showing them places,” Rohbar said. In Afghanistan, girls are not allowed to go to school beyond sixth grade, women are generally not allowed to work, get driver’s licenses or even spend time in public spaces. When they do, they must fully cover their bodies and faces.

Rohbar gives the same pep talk to all of the women she resettles from Afghanistan.

“I tell them, ‘You came this far, you better pick up all the goody bags from here. You came for education, work, and it will be useless if you don’t do anything, if you just do what you did back home. If you don’t take advantage after sacrificing everything — your home! — it will all be in vain for you.’”

In time, Madina would be able to participate in the women’s groups that Rohbar organizes. She could get help learning English and even enroll in adult education if she wanted to. But not yet.

“In the beginning, when they arrive, it’s overwhelming,” Rohbar said.

April 4, 2025: A new home — but what happens next?

A little over a month since the family arrived in the U.S., they finally had their own apartment. It was a walk-up on the second and third floors of a house in New Haven, near the idyllic Westville neighborhood. IRIS helped them find the apartment with four small bedrooms, overlooking a cemetery, just a few blocks from Edgewood Park.

Madina had pains in her belly the night before. They still had no furniture, just a few rugs and cushions for the living room floor and the hallway.

But the family seemed lighter. Rahim’s English was improving, and he could express himself without a relative at hand to translate.

“Right now, I’m good. The only problem is work, my wife is sick, my daughters, my son (needs to) go to school,” Rahim said. He couldn’t get his family around without a driver’s license. “I have appointments … if some people is not busy they coming (to drive me). My brother, my cousin.”

Mostly, the family stayed inside.

But today, with the sun out, Rahim decided to take them to the playground while Madina stayed with Asma, the youngest, at home. Rahim wrapped Asia and Asra in thick black parkas. Serwat and Alia, the oldest, helped their siblings tie their shoelaces. Finally, the kids jumped down the stairs and onto the sidewalk. Serwat retrieved a double stroller, and Rahim convinced the youngest girls to ride.

Daffodils and the pink cherry blossoms, the first of the season, opened their faces to the sun. Suddenly, desperate tears were rolling down Alia’s face. She wanted to climb out of the stroller and pick flowers from a manicured bed. She quieted when her father handed her a small, purple flower.

Jennifer Huebner, Sayed Rahim and his son Serwat walk towards the Mauro-Sheridan Magnet School on May 1, 2025. Credit: Shahrzad Rasekh / CT Mirror

May 1, 2025: First day of school in four years

Serwat got up early. He took a shower and sprayed himself with cologne, gelled his hair and combed it neatly to the side. Today would be his first day in a brick and mortar school in four years.

After the exit of U.S. armed forces from Afghanistan in 2021, the region of Khost where the family lived fell to Taliban control. Rahim decided to keep Serwat, then 7, at home. His school was 10 kilometers away, and the route between had become too dangerous to risk the journey. He was able to take classes during the few months the family spent at the Qatar refugee camp, but today was different: a new desk all to himself in Lauren Bitterman’s fifth-grade classroom at the Mauro-Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School in New Haven.